Why You Should Move and Exercise With Your Feet Straight-(er)

Let’s just say it outright: having full access to your body’s potential is harder than it sounds. This is especially true as modern people. Let’s face it, sometimes it’s just not practical to squat barefoot on the subway or in the boardroom. In the well-defined tug-of-war that is nurture vs. nature, we can change the “nurture” to be “shaped by the environment” and “nature” to mean, what is it a human being is supposed to be able to do given our 2.5 million years old physiology? One thing we do know though is that the world’s fastest runners, highest jumpers, most successful cyclists all share one trait – their feet are straight when they move and exercise.

Use It or Lose It

One of the aspects of human physiology that is underappreciated is the dynamic relationship between the actual physical loads on the human body and how the body responds. The easiest place to appreciate this “nurture affects nature” dynamic is in the bones of the human body. In the late 19th century, German surgeon and anatomist Julius Wolff described how the bones of a healthy person reflected the loads under which they were placed. If loading on a particular bone increases, the bone will remodel itself over time to become stronger to resist that sort of loading.

“Use it or lose it”.

-Wolff’s Law

We tend to think of loading as lifting weights or jumping. But loading can also mean the absence of strong forces in the boney tissues. In the 1990s, osteoporosis became a “public health crisis.” Originally we told people that were susceptible to bone loss to up their calcium and magnesium and to walk more. This, of course, turned out to be an incomplete recipe for correcting this problem. The real solution had to include higher than bodyweight forces. We needed to jump and land AND have the right substrates on hand in order for those bones to remodel and become stronger. Wolff’s law is the original “use it or lose it” philosophy. “But isn’t this article about foot position?” It is, but we need some context first.

“You are as old as your feet”

– Russian proverb

What is Normative?

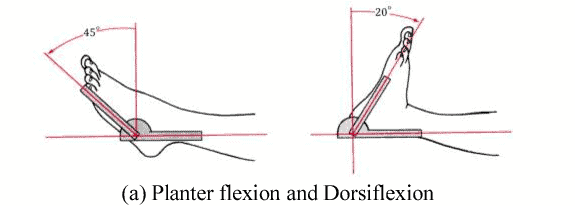

As we begin to lay out our case for what “normative human function” is, we can draw from any number of sources. By normative, we don’t mean normal. We mean, the expected ranges of motion across the whole spectrum of human body type (without the presence of pathology or injury). For example, the American Academy of Orthopedic Surgeons suggests that “standard” ankle dorsiflexion (flexing your foot towards your shin) should be expected to be 20 degrees. Standing requires zero dorsiflexion by comparison. If you were laying on your stomach and someone tried to flex your foot towards your shin, expected would be 20 degrees. The gold standard for physical therapy (Norkin and White) also suggests that 20 degrees are expected. There are a couple of other reference sources that suggest a bit more, but I appreciate that these values of ankle motion are a bit more on the conservative side. See fig (a) below.

Standardized ranges of motion can be thought of as context-free “snapshots” of human capacity. Because these body measurements are observed without the context of the rest of the body and without actual loaded movement, they are useful but incomplete. Knowing how far the steering wheel will rotate when the car isn’t moving is nice, but it doesn’t really say anything about how responsive the steering is at speed or how well the car drives. It’s clearly important, but by itself, it’s incomplete information about the system as a whole.

If the expected range of motion when flexing the ankle with a bent knee is 20 degrees, the first question we should ask is, “what does squatting look like if I’m missing all or almost all of my ankle dorsiflexion?” You can certainly squat down partway with no ankle range of motion (your lower leg will be very vertical) and your torso will have to bend forward at the waist to stay balanced, but you can do it. This zero ankle motion squat will make it harder to be in very athletic shapes (tough to compete looking at the floor with your hips hinged into a deep hip hinge) and it certainly isn’t ideal for keeping a barbell on your shoulders for a front squat. I will repeat, it is possible.

It turns out, however, that being able to flex your ankle is actually quite useful for athletic movement and even activities of daily living, like squatting with 100 kg on your shoulders or squatting to the toilet. And, when you can appropriately flex your ankle, you can move and exercise with your feet straight…which is ideal…

We have movement genius built into our DNA

The next question sets itself up. Don’t people squat and move throughout their day just fine without having full access to their ankle range of motion? You bet we do.

Enter: Compensation. Humans are some of the most clever animals on the planet when it comes to creating viable solutions to complex problems. The human brain is the most complex structure in the known universe. It happens to be attached to a body that has been evolving for more than a couple of million years in its more modern form. We are built to move and move at all costs. Our bodies are extraordinary in their capacity to continue to move in even the most austere conditions. Our very survival used to be predicated on being able to hunt, fight, gather and carry sustenance, and reproduce. Our bodies aren’t fragile. On the contrary, our bodies get better and stronger when they are stressed. They are anti-fragile.

“Muscles and tissues are like obedient dogs.”

– Pediatric PT saying

There is also a flip side to the incredible adaptation abilities of our bodies. Remember when we described “nature” as “shaped by our environment?” The same mechanisms that allow us to adapt so easily to difficult environments and loads, can work against us if we don’t appreciate the implications of our anti-fragile selves. For example, if we fail to move in ways that are consistent with the environmental demands of our evolutionary selves, we may find that we may lose access to ranges of motion that aren’t regularly touched. Can you squat all the way down to the ground while keeping your heels on the ground? I bet you could when you were a toddler. It’s so common for children to be able to perform this simple movement, in fact, that it is a red flag if they are unable.

So what changed? Moreover, when did it change? Overnight? All of a sudden? Do you remember a moment when you no longer could perform this fundamental human movement?

The chances are that as you aged, your movement behaviors changed as you began to interact differently with the world around you. For example, you probably moved from ground-based play exclusively, to more time spent sitting in a chair at a table. You also moved from being barefoot nearly all the time to wearing whatever shoes your family provided for you. Were those shoes flat or did they have a thicker heel than they did a toe? Were you aware that you might have suddenly and radically changed not only how your feet interacted with the ground, but how far your heel was now off the ground?

While it may be difficult to imagine that these seemingly insignificant environmental nudges to your physiology actually aggregate into expressed changes in movement outputs, we must consider that they are potentially shaping us over a time span of years to decades. Imagine missing a night of brushing your teeth. This is quite reasonable if you’ve ever been to college and pulled an all-nighter studying, or worked a graveyard shift, or even taken a red-eye cross country flight. It’s probably not really that big a deal to your dental health. But, what would happen if you started missing days regularly, or even weeks? I bet the results would be pretty self-evident, and relatively quickly. The same feedback mechanisms, unfortunately, do not equally manifest themselves in the human body. We might begin to experience changes in our tissue systems and never really be confronted with the potential implications of these changes, sometimes ever.

Remember, human beings are savage survival machines. Our bodies are designed to last a hundred years, buffer the ravages and degradation of life and injury, and still function to the last. The problem with this incredible gift is when we come to believe that what we are doing and how we are doing it, or how we are moving or not moving, is sustainable given that we haven’t had any “problems”. Add to this a super-computer brain that is designed to make do with what it has to work with, and it’s easy to confuse “good enough” for “what is it I should be able to do again?”

Imagine what an advantage it is to have a body that can cope with changes in its mechanical expression of movement by instantaneously creating workarounds. You’d still be able to walk around without any movement in your ankles (albeit with less efficiency, speed, and balance) for example. Kids with early signs of muscular dystrophy create brilliant solutions for getting up off the ground with straight legs and very little leg strength. In persons with cerebral palsy, altered changes in the brain’s ability to coordinate movement is overridden by the same brain, the body creates stability and again retains locomotion.

The former examples may seem extreme, but they illustrate how well our bodies can adapt to significant changes in our fundamental biology. What then is the body’s compensation or workaround strategy for missing ankle range of motion?

We turn our feet out. We walk like ducks and simply negate our missing ankle and foot function by walking around the ankle joint and rolling across the foot. As a survival strategy, this is pretty brilliant. But, it begs the existential question, “Is survival enough?”

The short answer is, sometimes? If I’m being chased by a hundred rabid chickens, I’ll use whatever strategy is available to me, thank you.

The rest of the time, survival as a baseline is a pretty low bar. And, it’s very short term oriented. If you ever want to run faster, farther, jump higher, cut quicker, or ride a bike faster, you are going to need to have your feet pointed straight ahead.

We recognize that full physiological function may not be on everyone’s priority list given that most of us just want to be able to go about our lives in a pain-free state. Heck, those bunions and demi-ankles may not ever really cause you grief. Go ahead and eat little chocolate donuts while smoking Lucky Strike cigarettes. I personally guarantee this won’t create immediate problems in your health. The operative word here is “immediate”. We should think about behaviors in the short term and in the long term. Sometimes it’s harder to do a better thing that ultimately pays off in terms of opportunity and potential you can’t yet appreciate.

Reality Check

We are forced to confront simple truths:

Do we accept lower levels of function because the potential down-stream consequences aren’t immediate?

Are we ok with the fact that survival compensation strategies limit force production, skill transferability, and movement economy, and potentially lead to dysfunction and pain?

Are we not sophisticated enough to adjust our environments to maintain the abilities with which nearly every child on the planet is born?

At The Ready State, we emphasize positions and techniques that maintain the full capacity of the human being. We have long maintained that the “best” athlete is the person that can pick up a new skill, the fastest. We choose shapes that reflect the full and normative expression of human physiology. We believe that technically good human movement is more robust than movements that contain survival compensations. We believe that movement skills are robust and that they should transfer across skills, sports, ages, and cohorts.

Missing ankle range of motion or having incomplete access to your physiology isn’t a value statement. It’s a reality. No one knows or can account for your personal injury history, environmental exposure, or movement learning. It’s not good or bad. But it is one or zero. This means you are either at full power and ability, or you have the opportunity to get even better (and believe me, I know lots of the world’s very best that can still get better).

In short, we believe and can demonstrate that moving, squatting, jumping, running, landing, and riding are all done better with feet that point straight ahead. Again, the best athletes on the planet move and exercise with their feet straight…did I say that again?

It may just be an issue of practice. And, it may be an issue of soft tissue restriction. Either way, muscles, and tissues are like obedient dogs. And, remember, at The Ready State, we have lots of content that can help with your tight ankles.

Feet straight-er, please.

TRS Virtual Mobility Coach

Guided mobilization videos customized for your body and lifestyle.

FREE 7-Day Trial