Creating an Unreasonable family

Although of course, we should include the “reasonable woman” in this statement, it does not change the mission, and actually only serves to broaden it. It’s up to parents and families to create an unreasonable family in their expectations for their children’s long term health.

Institutions and organizations may support this mission, but we must begin with what we can execute today to best serve and protect our children’s health and well-being. That starts with you, your family, your circle of friends, your community, etc.

It’s clearly overdue. Grab your neighbor and get on board.

Why you need to become unreasonably active as a family

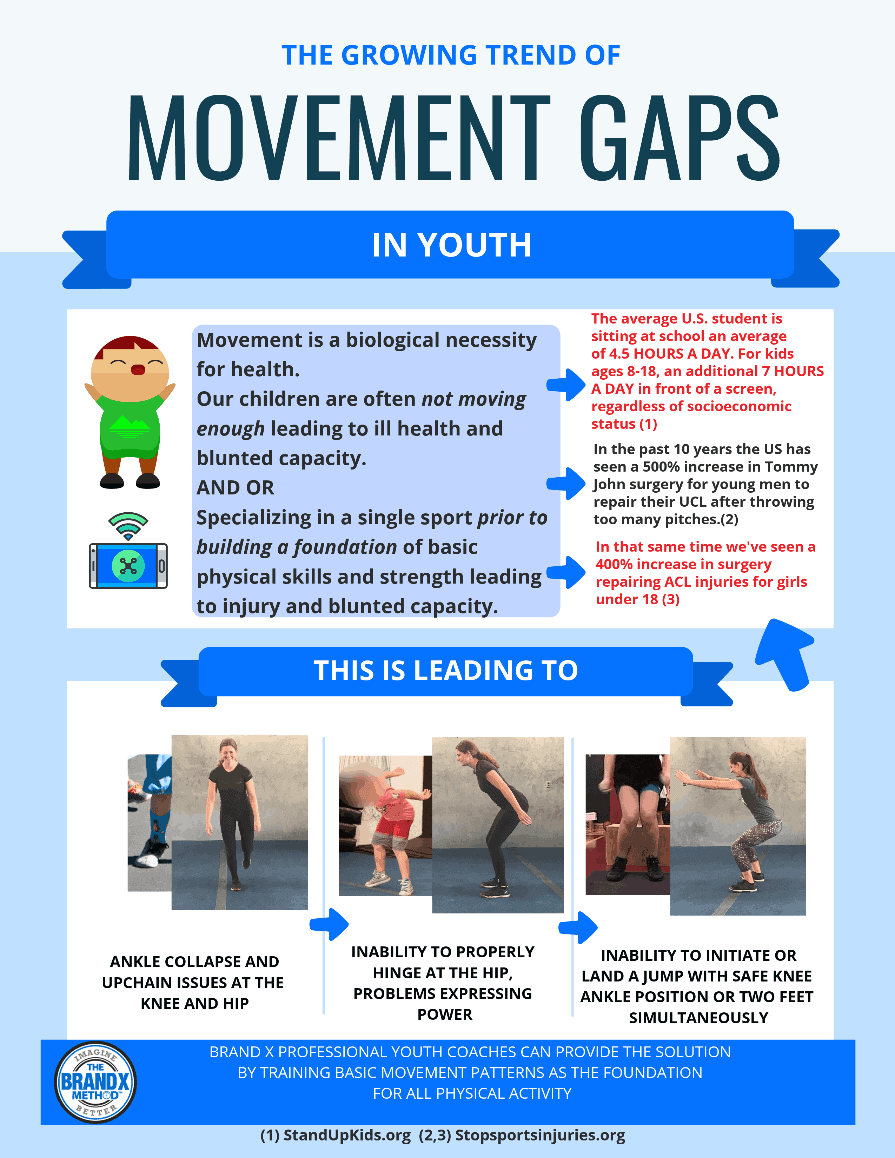

Here’s a summary of why you MUST create the family schedule to emphasize movement, play, and strength work for your children.

- Technology and sleep deprivation

- Increasing substitution of physical activity for sedentary tech time

- Lack of play and the associated increase in depression and anxiety, inability to adapt to new situations, reduction in creative problem solving

- Lack of play and social adaptation, lack of healthy social development

- Sedentary lifestyle, movement gaps, obesity, and type 2 diabetes

- Early sports specialization and overuse injury prevention

Many of you may already be familiar with some of the following statistics and research reflecting the state of children’s health and projected future health, but they bear repeating.

Technology’s negative impact on teen sleep

“[T]eens who spent three or more hours a day on electronic devices were 28% more likely to get less than seven hours of sleep, and teens who visited social media sites every day were 19% more likely not to get adequate sleep… The number of teens who don’t sleep enough goes up after two or more hours a day of electronic device use and skyrockets from there… An extensive meta-analysis of studies on electronic device use among children found similar results: children who used a media device before bed were more likely to sleep less than they should, more likely to sleep poorly, and more than twice as likely to be sleepy during the day.” (1)

Reducing teen tech usage can be accomplished by substituting tech-centered activities for movement-based activities that do not require—or better yet—do not even allow for tech usage.

Lack of play, declining socialization, mental health and exposure to normal human movement

“[Dr. Peter] Gray sees the loss of playtime as a double whammy: we have not only taken away the joys of free play, we have replaced them with emotionally stressful activities. ‘[A]s a society, we have come to the conclusion that to protect children from danger and to educate them, we must deprive them of the very activity that makes them happiest and place them for evermore hours in settings where they are more or less continually directed and evaluated by adults, settings almost designed to produce anxiety and depression.’” (2)

The importance of play, including risky play (3), as a catalyst for healthy child development, can no longer be ignored. Adult efforts to protect our children, to keep our children safe and sound, maybe having the opposite effect. The remarkable decline in free play—and in risky play particularly—for more than the last half-century has been accompanied by a dramatic increase in all kinds of childhood mental disorders, especially emotional disorders. (4)

“Studies of factors supporting play and mental health have focused on children’s formation of secure emotional attachments and on the role of stress. Extensive evidence has connected the formation of secure emotional attachments early in a child’s life to healthy brain development, the regulation of emotions, the ability to show empathy, the ability to form emotional relationships (including friendships with others), emotional resilience, and to playfulness. Children’s playfulness, in turn, has been shown to have a central role in the formation and maintenance of friendships, which are of crucial importance for healthy social and emotional development.

“Secure emotional attachments have been shown to be fundamental in supporting children’s ability to cope with stress and anxiety. Several studies in this area have made the important distinction between stress that is toxic, and stress that is positive. Children with insufficient emotional support and in relentlessly stressful situations arising from poverty, malnourishment, parental stress, or inadequate parenting are substantially more likely to feel toxic stress. Unsurprisingly, this type of stress is associated with mental health problems and low amounts of play. Conversely, children living in emotionally supportive and stimulating environments that nevertheless contain elements of uncertainty, or so-called positive stress, are more likely to be playful and emotionally resilient.” (5)

Sedentary lifestyle

On average, US students sit at school about 4.5 hours a day. For kids, ages 8-18, you can add to that an additional 7 hours a day in front of a screen, plus more time spent sitting to eat and to travel places. This means modern kids are spending up to 85% of their waking hours sitting. (6)

Obesity and long-term health

Since 1980, the prevalence of severe obesity in children, ages 2-19, has tripled from 6% to almost 20% (7), and there are currently over 90 million people affected by obesity in the US of which 18 million are children. (8) These trends have experts predicting that about 60% of the population will be obese by 2048. (9) Meanwhile, obesity-related diseases, such as Type 2 diabetes, liver disease, and cardiovascular disease, once rare in children, are now increasingly common. (10, 11, 12)

Early sports specialization

The prevalence of youth sports injuries is well documented. The notion of youth sports injury has been normalized in popular culture and should be a red flag to all that something is very wrong with the status quo. For example, take this ad deploying the memory of a child on crutches after a presumed sports injury to evoke nostalgia:

But perhaps the reason that these injuries are taken for granted is that year-round intensive and competitive play and early specialization are staples in youth sports.

Consider that there is a 500% increase in risk for surgery for baseball players that pitch more than 8 months of the year and a 400% increase in risk observed for those that throw more than 80 pitches per game. (13) Further, not only are younger and younger athletes experiencing this big-league problem but, incredibly, misunderstanding of Tommy John’s surgery outcomes leads many of them to want that surgery in the absence of injury. (14)

Check out the following statistics from STOP Sports Injuries:

- High school athletes account for an estimated 2 million injuries and 500,000 doctor visits and 30,000 hospitalizations each year.

- More than 3.5 million kids under age 14 receive medical treatment for sports injuries each year.

- Children ages 5 to 14 account for nearly 40 percent of all sports-related injuries treated in hospitals. On average the rate and severity of injury increase with a child’s age.

- Overuse injuries are responsible for nearly half of all sports injuries to middle and high school students.

- Although 62 percent of organized sports-related injuries occur during practice, one-third of parents do not have their children take the same safety precautions at practice that they would during a game.

- Twenty percent of children ages 8 to 12 and 45 percent of those ages 13 to 14 will have arm pain during a single youth baseball season.

- Injuries associated with participation in sports and recreational activities account for 21 percent of all traumatic brain injuries among children in the United States.

- According to the CDC, more than half of all sports injuries in children are preventable.

- By age 13, 70 percent of kids drop out of youth sports. The top three reasons: adults, coaches, and parents.

- Among athletes ages, 5 to 14, 28 percent of football players, 25 percent of baseball players, 22 percent of soccer players, 15 percent of basketball players, and 12 percent of softball players were injured while playing their respective sports.

- Since 2000 there has been a fivefold increase in the number of serious shoulder and elbow injuries among youth baseball and softball players.

Chin up, because all this is not that hard to fix for yourself, your children, and your family’s future, as long as you are willing to take the path of the unreasonable family and become a beacon for change.

- The development of optimal physical health requires movement. (15, 16, 17)

- Aspen Institute’s Project Play indicates that physically active youngsters have up to 40% higher test scores and are less likely to engage in high-risk behaviors.

- The development of optimal mental health requires free play. (2-5, 18, 19)

- Healthy, enduring sports specialization and sports participation require a broad movement experience as the foundation to limit potential injury and support athleticism. (20, 21, 22, 23)

- Strength training helps. (24, 25, 26, 27, 28, 29)

Given these facts…

Here is the unreasonable plan – Move, Play, and Strengthen

1. Move more

Make sure your kids are up and doing stuff consistently. A broad variety of physical things is best. (30, 31, 32, 33) Outdoor activity provides extra benefits. (34, 35) Create activities, adventures, and opportunities to experience the entire library of human movement and capacity. Encourage your kids to climb, throw, carry, jump, swim, roll, toss, leap, glide, bound, spin, pull, push, swing, balance, and hop in as many novel ways as possible. Consider a program, such as The Brand X Method, which not only addresses primal and functional movement patterns with an age-appropriate mechanical emphasis and the full biopsychosocial spectrum of youth development but is also a supervised strength program designed specifically for children and teens. This guarantees that your child is exposed to the full library of human movement.

2. Play one hour every day

Play promotes exploration and experimentation, enhances learning opportunities for problem-solving and skill development, encourages cooperation, and enables contact with and adjustment to novel situations. This leads to improved mental health and social development.

Encourage play without rules and little structure. Allow kids to move over and around objects any way they want, creating their own unique movement solutions to movement problems. Social play with peers—and no adults, timelines, or expectations—are optimal.

3. Strengthen a minimum of one hour twice a week

Enroll your kids in a youth strength program administered by coaches educated specifically in a youth strength program, and implementing a program specifically designed for kids and teens. (27)

Strength training for athletes and non-athletes provides better health through life as well as support for both injury prevention and accelerated athleticism. (36)

4. Additional ideas

- Get involved with PTA to insist on having kids move more throughout the school day in your community. (StandUPKids)

- Seek more education on the subject, enlighten your neighbors, and start a local group for a change.

- Start today. We can’t rely on institutions for the fix. In the youth sports complex, systems are entrenched, and coaches are often hired and paid to win, not ensure longevity and motivation.

Become UNREASONABLE. Move, play, and strengthen your family.

Brand X resources:

Book a call with the Brand X founders.

Brand X youth coaching education: the Professional Youth Coach Certification

Art of Growing Up Strong™ seminars online (coming Sept 2019!) and live courses

Brand X Training Center locations

Become a Brand X Youth Training Center

References

(1) Twenge J.M. iGen: Why Today’s Super-Connected Kids Are Growing Up Less Rebellious, More Tolerant, Less Happy—and Completely Unprepared for Adulthood—and What That Means for the Rest of Us. NY: Atria Books, 2017.

(2) Entin E. All work and no play: why your kids are more anxious, depressed. The Atlantic. 12 October 2011. Available at https://www.theatlantic.com/health/archive/2011/10/all-work-and-no-play-why-your-kids-are-more-anxious-depressed/246422/. Accessed 20 August 2019.

(3) Hansen Sandseter E.B. and Ottesen Kennair L.E. Children’s risky play from an evolutionary perspective: the anti-phobic effects of thrilling experiences. Evolutionary Psychology 9(2): 257-284, 2011.

(4) Gray P. Risky play: why children love it and need it. Psychology Today. 7 April 2014. Available at https://www.psychologytoday.com/us/blog/freedom-learn/201404/risky-play-why-children-love-it-and-need-it. Accessed 21 August 2019.

(5) Whitebread D. Free play and children’s mental health. The Lancet: Child & Adolescent Health. November 2017. Available at https://www.download.thelancet.com/journals/lanchi/article/PIIS2352-4642(17)30092-5/fulltext. Accessed 20 August 2019.

(6) Standing vs sitting. Stand Up Kids. Available at https://standupkids.org/standing-vs-sitting/. Accessed 20 August 2019.

(7) Ogden C.L. et al. Trends in obesity prevalence among children and adolescents in the United States, 1988-1994 through 2013-2014. Journal of the American Medical Association 315(21): 2292-2299, 7 June 2016.

(8) Ogden C.L. et al. Prevalence of childhood and adult obesity in the United States, 2011-2012. Journal of the American Medical Association 311(8): 806-814, 26 February 2014.

(9) Ward Z.J. et al. Simulation of growth trajectories of childhood obesity into adulthood. New England Journal of Medicine. 377(22): 2145-2153, 2017.

(10) Kit B.K. et al. Prevalence of and trends in dyslipidemia and blood pressure among US children and adolescents, 1999-2012. Journal of the American Medical Association Pediatrics 169(3): 272-279, 2015.

(11) Kumar S. and Kelly A.S. Review of childhood obesity: from epidemiology, etiology, and comorbidities to clinical assessment and treatment. Mayo Clinic Proceedings 92(2): 251-265, February 2017.

(12) Lightwood J. et al. Forecasting the future economic burden of current adolescent overweight: an estimate of the coronary heart disease policy model. American Journal of Public Heath 99(12): 2230-2237, December 2009.

(13) Hodgins J.L., Vitale M., and Arons R.R. Epidemiology of medial ulnar collateral ligament reconstruction: a 10-year study in New York state. American Journal of Sports Medicine 44(3): 729-734, 2016.

(14) Andrews J.R. and Yaeger D. Any Given Monday: Sports Injuries and How to Prevent Them, for Athletes, Parents, and Coaches—Based on My Life in Sports Medicine. NY: Scribner, 2013.

(15) Harvard Men’s Health Watch. Walking: your steps to health. Available at https://www.health.harvard.edu/staying-healthy/walking-your-steps-to-health. Accessed 21 August 2019.

(16) Pontzer H. Evolved to exercise. Scientific American 320(1): 22-29, January 2019.

(17) Committee on Physical Activity and Physical Education in the School Environment. Physical activity and physical education: relationship to growth, development, and health. In Educating the Student Body: Taking Physical Activity and Physical Education to School. Kohl H.W. III and Cook H.D. eds. Washington, DC: National Academies Press, 2013.

(18) Gray P. The decline of play and rise in children’s mental disorders. Psychology Today 26 January 2010. Available at https://www.psychologytoday.com/us/blog/freedom-learn/201001/the-decline-play-and-rise-in-childrens-mental-disorders. Accessed 21 August 2019.

(19) Gray P. The decline of play and rise of psychopathology in children and adolescents. American Journal of Play 3(4): 443-463, Spring 2011.

(20) Fransen J. et al. Differences in physical fitness and gross motor coordination in boys aged 6-12 years specializing in one versus sampling more than one sport. Journal of Sports Sciences 30(4): 379-386, 2012.

(21) Côté J. et al. The benefits of sampling sports during childhood. Physical and Health Education Journal 74(4): 6-11, 2009.

(22) Fraser Thomas J., Côté J., and Deakin J. Youth sport programs: an avenue to foster positive youth development. Physical Education and Sports Pedagogy 10(1): 19-40, February 2005.

(23) Côté J., Lidor R., and Hackfort D. ISSP position stand: to sample or to specialize? Seven postulates about youth sport activities that lead to continued participation and elite performance. International Journal of Sport and Exercise Psychology 7(1): 7-17, 2009.

(24) Faigenbaum A.D. et al. Comparison of 1 and 2 days per week of strength training in children. Research Quarterly for Exercise and Sport 73(4): 416-424, 2002.

(25) Faigenbaum A.D. et al. Youth resistance training: updated position statement paper from the National Strength and Conditioning Association. Journal of Strength and Conditioning Research 23(Supp 5): S60-S79, August 2009.

(26) Faigenbaum A.D. et al. The effects of different resistance training protocols on muscular strength and endurance development in children. Pediatrics 104(e5), 1999.

(27) Council on Sports Medicine and Fitness. Strength training by children and adolescents. Pediatrics 121(4): 835-840, 2008.

(28) Lloyd R.S. et al. UKSCA position statement: youth resistance training. UK Strength and Conditioning Association 26: 26-39, Summer 2012.

(29) Faigenbaum A.D., MacDonald J.P., and Haff G.G. Are young athletes strong enough for sports? DREAM on. Current Sports Medicine Reports 18(1): 6-8, January 2019.

(30) Whitehead M, ed. Physical Literacy: Throughout the Life Course. NY: Routledge, 2010.

(31) Balyi I., Way R., and Higgs C. Long-Term Athlete Development. Champaign, Ill: Human Kinetics, 2013.

(32) Lloyd R.S. and Oliver J.L. The youth physical development model: a new approach to long-term athletic development. Strength and Conditioning Journal 34(3): 61-72, June 2012.

(33) Lloyd R.S. et al. Long-term athletic development – Part 1: a pathway for all youth. Journal of Strength and Conditioning Research 29(5): 1439-1450, May 2015.

(34) McCurdy L.E. et al. Using nature and outdoor activity to improve children’s health. Current Problems in Pediatric and Adolescent Health Care 40(5): 102-117, May 2010.

(35) Godbey G. Outdoor recreation, health, and wellness: understanding and enhancing the relationship. RFF Discussion Paper No. 09-21, 6 May 2009.(36) Zwolski C., Quatman-Yates C., and Paterno M.V. Resistance training in youth: laying the foundation for injury prevention and physical literacy. Sports Health 9(5): 436-443, September-October 2017.

TRS Virtual Mobility Coach

Guided mobilization videos customized for your body and lifestyle.

FREE 7-Day Trial